Details

Program staff contact: Maria Icenogle

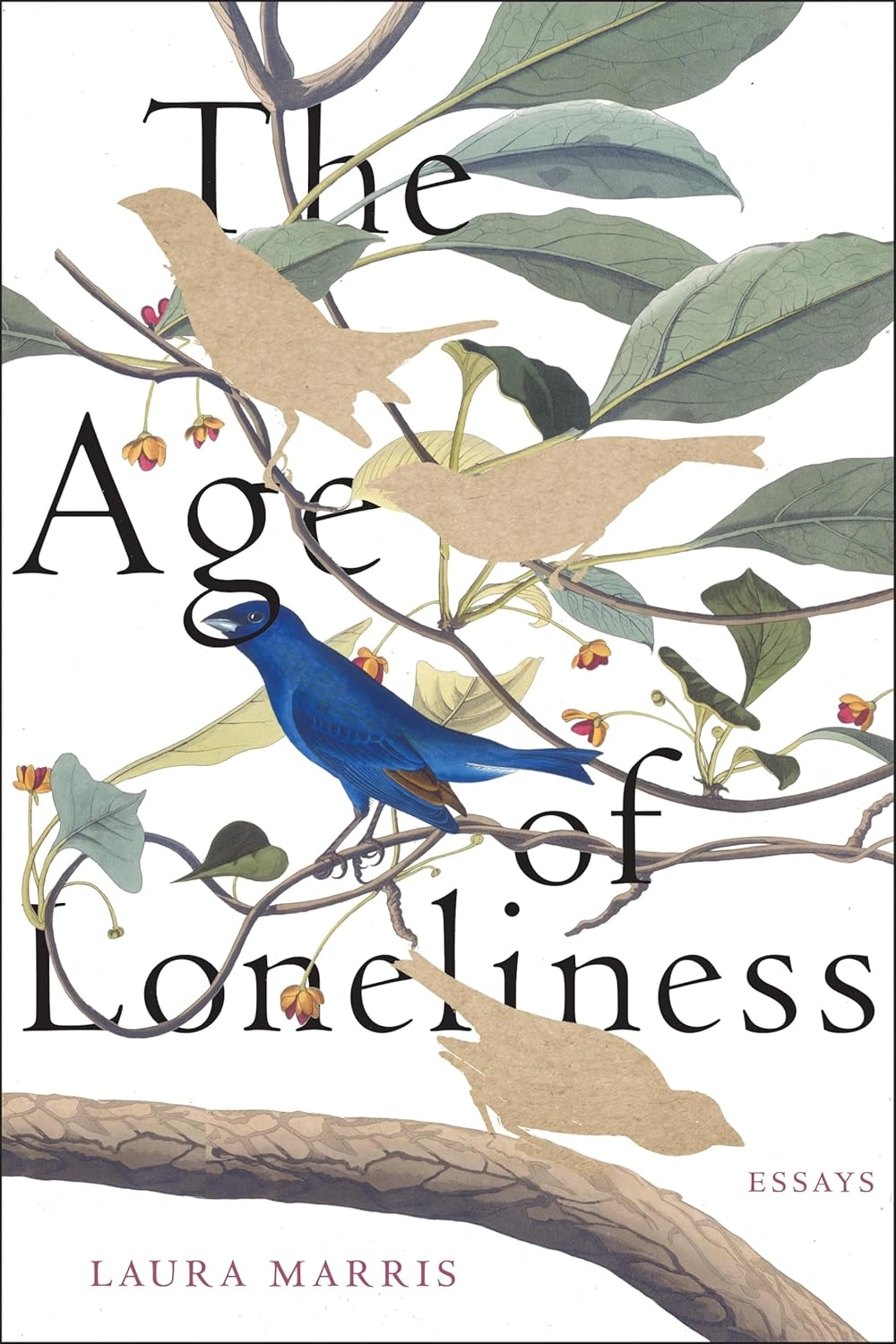

Laura Marris is an essayist, poet, and translator. Her work has appeared in The Kenyon Review, The Believer, Harper’s, The New York Times, The Paris Review Daily, The Yale Review, Words Without Borders and elsewhere. She has received fellowships from MacDowell, a Katharine Bakeless Fellowship from the Bread Loaf Writer’s Conference, and a grant from the Robert B. Silvers Foundation. Her first book, The Age of Loneliness, was published by Graywolf 2024. She teaches creative writing at the University at Buffalo.

In this debut essay collection, Laura Marris reframes environmental degradation by setting aside the conventional, catastrophic framework of the Anthropocene in favor of that of the Eremocene, the age of loneliness, marked by the dramatic thinning of wildlife populations and by isolation between and among species. She asks: how do we add to archives of ecological memory? How can we notice and document what’s missing in the landscapes closest to us?

Filled with equal parts alienation and wonder, each essay immerses readers in a different strange landscape of the Eremocene. Among them are the Buffalo airport with its snowy owls and the purgatories of commuter flights, layovers, and long-distance relationships; a life-size model city built solely for self-driving cars; the coasts of New England and the ever-evolving relationship between humans and horseshoe crabs; and the Connecticut woods Marris revisits for the first time after her father’s death, where she participates in the annual Christmas Bird Count and encounters presence and absence in turn.

Vivid, keenly observed, and driven by a lively and lyrical voice, The Age of Loneliness is a moving examination of the dangers of loneliness, the surprising histories of ecological loss, and the ways that community science―which relies on the embodied evidence of “ground truth”―can help us recognize, and maybe even recover, what we’ve learned to live without.